How would consumers react if their cellphone bore a product label that read, “Manufactured with metals frequently sourced from non-democratic countries, mined with extreme indifference to the environment and worker safety with profits going to support terrorism and the suppression of basic human rights”?

Protecting Supply Chains and Prosperity: The Case for Reducing US Dependency on Foreign Critical Minerals

Image courtesy of Dane Rhys

Expert Opinion Article by Eric J. Mears, Vice President, Haley & Aldrich

The US is blessed with abundant mineral resources. We enjoy a well-educated workforce, reliable transportation, robust infrastructure, and reasonably predictable political and legal systems. We also have a diverse economy, a fair tax structure, and strong manufacturing and business sectors. When compared to other mineral producing regions across the globe, the US is easily one the most attractive locations for mineral exploration and the development of mining projects.

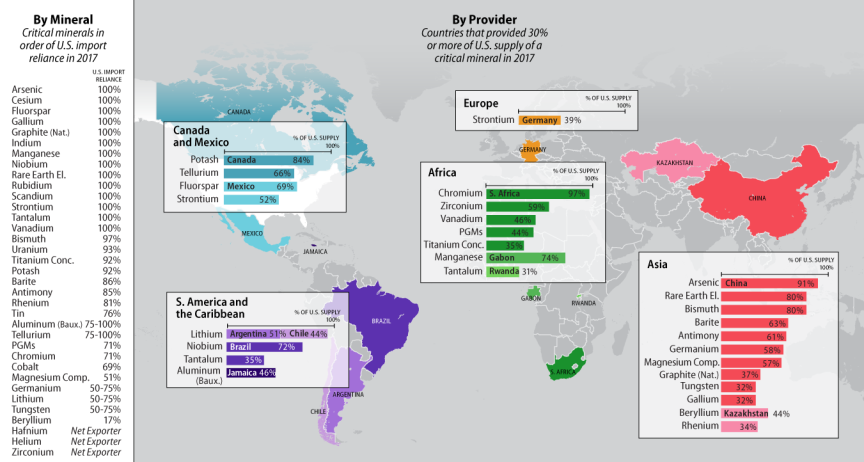

Yet, mineral production in the US is not keeping pace with world markets or our own domestic demands for minerals. Consequently, our exponential growth in technology, defense, housing, green energy, and infrastructure has become alarmingly dependent on critical minerals produced overseas, even when the resources we need are in our backyard.

Why is this a problem?

Many of the critical minerals used in manufacturing today are sourced from non-democratic countries; extracted from poorly regulated mines that exploit children or slave labor; enrich despots, terrorists, or other criminals; or decimate natural resources, native people’s lands, and wildlife habitats. And although US mining, defense, and manufacturing leaders have been waving red flags for several decades, consumers are largely unaware of the geopolitical implications of sourcing critical minerals outside of the US. Most consumers know more about where their broccoli is sourced than virtually every critical mineral used in electronics and clean energy, defense, and manufacturing products – so there is no demand for change.

Source: Congressional Research Service, based on USGS Minerals Commodities data, 2019

Why haven’t we addressed the problem?

Aside from consumer indifference, we don’t produce more of our own resources because well-meaning political, legal, and regulatory systems have been misused to the point where it becomes easier for mining projects to be offshored to less regulated, more politically pragmatic, and less litigious mining jurisdictions. In 2010, the federal government acknowledged that the rapid expansion of materials-intensive industries like clean energy and defense put critical materials at “risk of unpredictable moments of short supply,” and more recently, the government has placed emphasis on understanding and addressing vulnerabilities in our critical minerals supply chain. However, despite this acknowledgement and emphasis, actions have been taken by all levels of government to systematically dismantle policies, agency actions, and programs that held promise for fairly regulating and streamlining critical mineral permitting and entitlement efforts such as the transparency and predictability of the National Environmental Policy Act review and authorization processes.

Unsurprisingly, even when projects have government support, economic and political issues get in the way of their coming to fruition. The current administration recently highlighted its support and funding for a multibillion-dollar research and development effort to determine if lithium can be extracted from geothermal brines in Imperial County, California. Before a single pound of lithium has been extracted, a newly authorized Lithium Valley Commission is already developing a royalty structure to collect profits from its future operations, and the California legislature hurriedly imposed an industry crushing tax on lithium production.

What can we do?

The reality is that the US can only reduce its dependence on foreign critical minerals when domestic mines capable of producing critical minerals are routinely permitted and operational. This means that consumers need to care about the ethics of mineral sourcing, that permitting agencies must be appropriately staffed and directed to efficiently permit mines, that non-governmental organizations have to collaborate more and litigate less, and that the government needs to dedicate more resources to cultivating a critical industry rather than creating additional obstacles to shut it down.

In other words, we have to dig our own way out of this problem.